From Imperative to Declarative in Flet: Migrating a Simple CRUD “User Manager”#

If you’ve been using Flet, you’ve probably built your apps the imperative way, maybe without even noticing. You flip visibility flags, set control values, update lists of controls and call page.update() - that is the imperative approach, meaning you change UI directly when handling events. Flet now supports a declarative style: stop mutating controls, change state instead, and Flet updates the UI automatically.

We’ll show the switch using a tiny CRUD “User Manager” app. First, the imperative version: UI-first, mutate controls, then update the page. Then the declarative rewrite: model-first, observable classes for data, components that return UI from state.

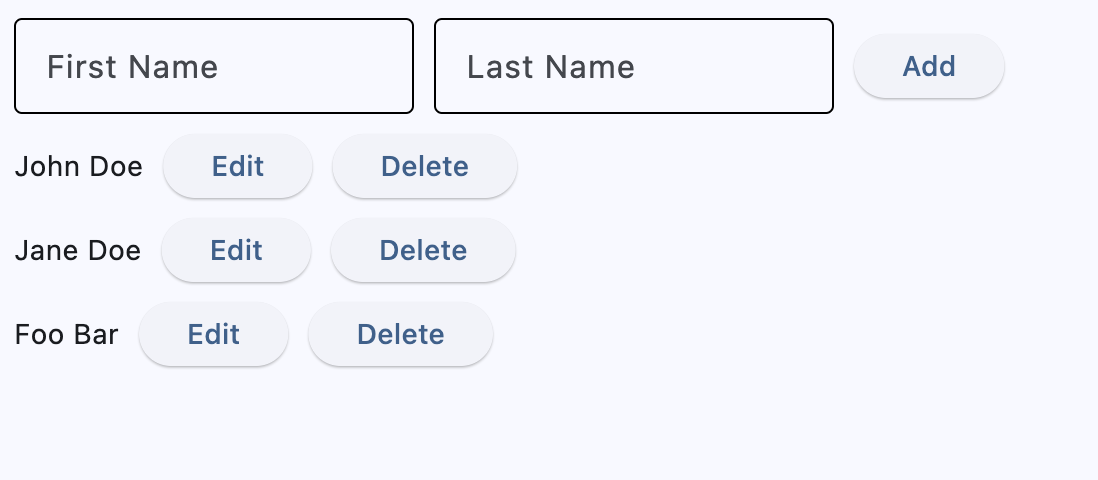

The behavior in both examples stays the same - in the app you can see the list of users, add user, inline edit with save/cancel buttons and delete. This is how this simple app looks in both examples:

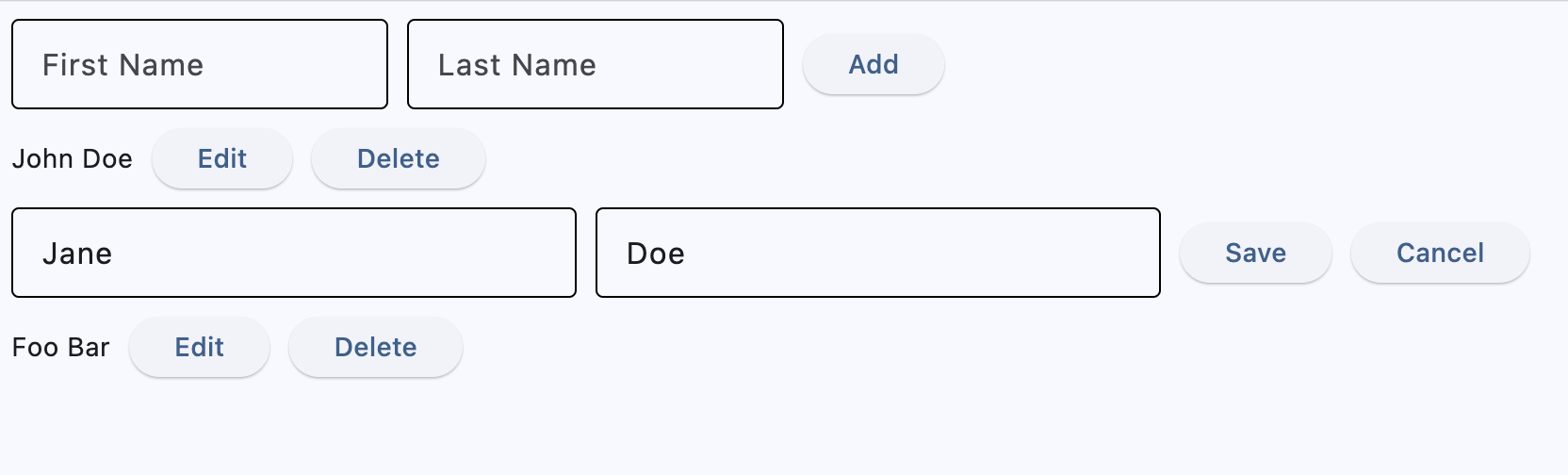

After clicking inline Edit button:

Example 1 — Imperative#

In the imperative version, you think UI-first: decide exactly how the screen should look, and how it should change on each button click. Event handlers directly toggle control properties (like visible, value), insert/remove controls, and then call page.update() to push those visual changes. Edit hides the read-only label and action buttons, shows inputs and Save/Cancel; Save copies text field values back into the label and restores the original view; Cancel just restores the original view; Delete removes the whole row from the page. In short, behavior is implemented by mutating controls and manually triggering re-renders, not by evolving a separate state model.

import flet as ft

class Item(ft.Row):

def __init__(self, first_name, last_name):

super().__init__()

self.first_name_field = ft.TextField(first_name)

self.last_name_field = ft.TextField(last_name)

self.text = ft.Text(f"{first_name} {last_name}")

self.edit_text = ft.Row(

[

self.first_name_field,

self.last_name_field,

],

visible=False,

)

self.edit_button = ft.Button("Edit", on_click=self.edit_item)

self.delete_button = ft.Button("Delete", on_click=self.delete_item)

self.save_button = ft.Button("Save", on_click=self.save_item, visible=False)

self.cancel_button = ft.Button(

"Cancel", on_click=self.cancel_item, visible=False

)

self.controls = [

self.text,

self.edit_text,

self.edit_button,

self.delete_button,

self.save_button,

self.cancel_button,

]

def delete_item(self, e):

self.page.controls.remove(self)

self.page.update()

def edit_item(self, e):

print("edit_item")

self.text.visible = False

self.edit_button.visible = False

self.delete_button.visible = False

self.save_button.visible = True

self.cancel_button.visible = True

self.edit_text.visible = True

self.page.update()

def save_item(self, e):

self.text.value = f"{self.first_name_field.value} {self.last_name_field.value}"

self.text.visible = True

self.edit_button.visible = True

self.delete_button.visible = True

self.save_button.visible = False

self.cancel_button.visible = False

self.edit_text.visible = False

self.page.update()

def cancel_item(self, e):

self.text.visible = True

self.edit_button.visible = True

self.delete_button.visible = True

self.save_button.visible = False

self.cancel_button.visible = False

self.edit_text.visible = False

self.page.update()

def main(page: ft.Page):

page.title = "CRUD Imperative Example"

def add_item(e):

item = Item(first_name.value, last_name=last_name.value)

page.add(item)

first_name.value = ""

last_name.value = ""

page.update()

first_name = ft.TextField(label="First Name", width=200)

last_name = ft.TextField(label="Last Name", width=200)

page.add(

ft.Row(

[

first_name,

last_name,

ft.Button("Add", on_click=add_item),

]

)

)

ft.run(main)

Example 2 — Declarative#

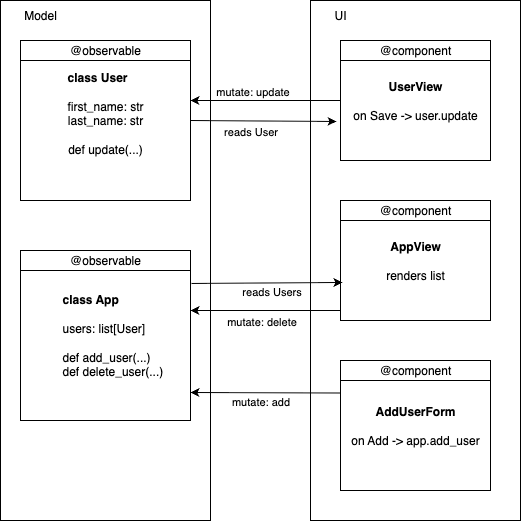

In the declarative version, you think model-first: the model is a set of classes, and the data their objects hold is the single source of truth. In our CRUD app, the model consists of User (persisted fields first_name, last_name) and a top-level App that owns users: list[User] plus actions like add_user(first, last) and delete_user(user). Both classes are marked @ft.observable, so assigning to their attributes (e.g., user.update(...), app.users.remove(user)) triggers re-rendering — no page.update().

The UI is composed as components marked with @ft.component that return a view of the current state. Each row decides whether to show a read-only view or an inline editor using its own short-lived, local values (hooks), while the durable data lives on the model objects. Event handlers update state only (e.g., modify a user or add/remove items), not the controls themselves; Flet detects those changes and re-renders the affected parts. In short: UI = f(state), with User and App providing the authoritative data.

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

import flet as ft

@ft.observable

@dataclass

class User:

first_name: str

last_name: str

def update(self, first_name: str, last_name: str):

self.first_name = first_name

self.last_name = last_name

@ft.observable

@dataclass

class App:

users: list[User] = field(default_factory=list)

def add_user(self, first_name: str, last_name: str):

if first_name.strip() or last_name.strip():

self.users.append(User(first_name, last_name))

def delete_user(self, user: User):

self.users.remove(user)

@ft.component

def UserView(user: User, delete_user) -> ft.Control:

# Local (transient) editing state—NOT in User

is_editing, set_is_editing = ft.use_state(False)

new_first_name, set_new_first_name = ft.use_state(user.first_name)

new_last_name, set_new_last_name = ft.use_state(user.last_name)

def start_edit():

set_new_first_name(user.first_name)

set_new_last_name(user.last_name)

set_is_editing(True)

def save():

user.update(new_first_name, new_last_name)

set_is_editing(False)

def cancel():

set_is_editing(False)

if not is_editing:

return ft.Row(

[

ft.Text(f"{user.first_name} {user.last_name}"),

ft.Button("Edit", on_click=start_edit),

ft.Button("Delete", on_click=lambda: delete_user(user)),

]

)

return ft.Row(

[

ft.TextField(

label="First Name",

value=new_first_name,

on_change=lambda e: set_new_first_name(e.control.value),

width=180,

),

ft.TextField(

label="Last Name",

value=new_last_name,

on_change=lambda e: set_new_last_name(e.control.value),

width=180,

),

ft.Button("Save", on_click=save),

ft.Button("Cancel", on_click=cancel),

]

)

@ft.component

def AddUserForm(add_user) -> ft.Control:

# Uses local buffers; calls parent action on Add

new_first_name, set_new_first_name = ft.use_state("")

new_last_name, set_new_last_name = ft.use_state("")

def add_user_and_clear():

add_user(new_first_name, new_last_name)

set_new_first_name("")

set_new_last_name("")

return ft.Row(

controls=[

ft.TextField(

label="First Name",

width=200,

value=new_first_name,

on_change=lambda e: set_new_first_name(e.control.value),

),

ft.TextField(

label="Last Name",

width=200,

value=new_last_name,

on_change=lambda e: set_new_last_name(e.control.value),

),

ft.Button("Add", on_click=add_user_and_clear),

]

)

@ft.component

def AppView() -> list[ft.Control]:

app, _ = ft.use_state(

App(

users=[

User("John", "Doe"),

User("Jane", "Doe"),

User("Foo", "Bar"),

]

)

)

return [

AddUserForm(app.add_user),

*[UserView(user, app.delete_user) for user in app.users],

]

ft.run(lambda page: page.render(AppView))

Mindset shift: UI = f(state)#

The core idea is determinism: given the same state, your component should return the same UI. Think in two phases:

-

Handle event → update state Event handlers change data only (e.g.,

set_is_editing(True),user.update(...)). They don’t hide/show controls or callpage.update(). -

Render → derive UI from state The component returns controls based on the current state snapshot. Because models are

@ft.observableand locals come fromft.use_state, Flet re-runs the component when state changes and re-renders the right subtree.

Declarative Building Blocks: Observables, Components, Hooks#

Below are the key pieces of the Flet framework that make the declarative approach work:

Observables — your source of truth#

@ft.observable marks a dataclass as reactive. When you assign to its fields (user.first_name = "Ada" or app.users.append(user)), Flet re-renders any components that read those fields - no page.update() calls. Use observables for persisted/domain data (things you actually save).

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

import flet as ft

@ft.observable

@dataclass

class User:

first_name: str

last_name: str

@ft.observable

@dataclass

class AppState:

users: list[User] = field(default_factory=list)

Components — functions that return UI#

@ft.component turns a function into a rendering unit. It takes props (regular args), may use hooks, and returns controls that describe the UI for the current state. Components do not imperatively mutate the page tree; they just return what the UI should look like now.

import flet as ft

@ft.component

def UserRow(user: User, on_delete) -> ft.Control:

# returns a row for the current snapshot of `user`

return ft.Row([

ft.Text(f"{user.first_name} {user.last_name}"),

ft.Button("Delete", on_click=lambda _: on_delete(user)),

])

Hooks — local, short-lived UI state#

Why they are needed: components are functions that re-run on every render. Plain local variables get reinitialized each time, and changing them doesn’t tell Flet to update the view. Hooks (e.g., ft.use_state) give a component a place to persist values across renders and a way to signal a re-render when those values change.

What hooks solve

- Persistence: locals reset on each render; hook state survives.

- Reactivity: modifying a local doesn’t refresh the UI; a hook’s setter schedules a re-render.

- Fresh values in handlers: event callbacks won’t see stale locals; they read the latest hook state.

Use hooks for short-lived, view-only concerns (like an “is editing?” flag or current input text) that belong to a single component. Use observables for durable app/domain data shared across components.

Example

# Broken: local resets every render and doesn't trigger updates

@ft.component

def CounterBroken():

count = 0

return ft.Row([

ft.Text(str(count)),

ft.Button("+", on_click=lambda _: (count := count + 1)), # no re-render

])

# Correct: persists across renders and re-renders when updated

@ft.component

def Counter():

count, set_count = ft.use_state(0)

return ft.Row([

ft.Text(str(count)),

ft.Button("+", on_click=lambda _: set_count(count + 1)),

])

Rule of thumb: if a value must survive re-renders and updating it should change the UI, don’t use a plain local — use hook state (for local UI) or an observable (for shared, persisted data).

Rewrite recipes (imperative → declarative)#

1) Visibility toggles → Conditional rendering#

# Imperative

self.text.visible = False

self.save_button.visible = True

self.page.update()

# Declarative

return (

ft.Row([...read-only...])

if not is_editing

else ft.Row([...edit form...])

)

2) Direct control mutation → Model mutation#

# Imperative

self.text.value = f"{first} {last}"

# Declarative

user.update(new_first_name, new_last_name)

3) page.update() everywhere → Nowhere#

- Imperative handlers end with

page.update(). - Declarative code updates observable fields or

use_statevalues and lets Flet re-render.

4) Handlers manipulate state, not the view#

5) Extract UI into components#

UserView= one row (read-only/editing)AddUserForm= small, reusable add form

Summary#

The declarative style makes your UI a straightforward function of your data. It may not be make a big difference for a very simple app, but as your screen grows, you’ll add state and components, not scattered mutations of controls in different places. The result: code that’s easier to understand, maintain, and change — without chasing visible flags or manual updates.